Can An. Mosquitoes Co-transmit both Malaria & LF?

|

| [Image credit: healthline.com] |

Ad: We offer a range of writing and research services. Find out more!

|

Definition of some key terms

LF: This is the abbreviated form of ‘lymphatic filariasis’, a disease characterized by swollen feet (elephantiasis). The

disease is popularly known as ‘elephantiasis’, although that is not the

accurate name for it. This is because the condition, elephantiasis is only a

symptom of LF.

Wuchereria

bancrofti: this is the causative organism

for LF.

Anopheles mosquito: This is a particular grouping of mosquitoes

commonly involved in the transmission of a number of insect-borne diseases.

Endophagic: Indoor biting

behaviour of mosquito.

Exophagic: Outdoor biting

behaviour of mosquito.

Researcher: D.I.

Introduction

In 2006 and 2008, respectively, an estimated 8.3 million and 3.2 million malaria cases were reported for Ghana (WHO, 2009).

Prevalence of LF is between 9.2 –

25.4% along the coast (Dunyo et al., 1996) and 20 – 40% in the northern

regions (Gyapong et al., 1996).

In 2006 and 2008, respectively, an estimated 8.3 million and 3.2 million malaria cases were reported for Ghana (WHO, 2009).

|

| [Image Credit: oyibosonline.com] |

LF prevalence in Achowa was

estimated to be 30 – 50 %, whilst that in Butre to be 10 – 30 %; an estimated

malaria prevalence of 10 – 30 % for Achowa and > 0 – 10 % for Butre

(Kelly-Hope et al., 2006).

Work done by Dunyo et al.

(1996) along the coast of Ghana revealed the presence of Anopheles gambiae

s.s., which Gyapong et al. (2005) reported to be involved in the

phenomenon of limitation, despite deployment of mass drug administration in the

area.

Ad: We offer a range of writing and research services. Find out more!

Ad: We offer a range of writing and research services. Find out more!

The vectors that play major roles

in malaria and LF transmission in Ghana are: Anopheles gambiae Giles,

and An. funestus Giles (Appawu et al., 1994 and Dzodzomenyo et

al. 1999).

Work done by Muturi et al.

(2006b) along the Kenyan coast revealed that Wuchereria-infected An.

gambiae s.l. had significantly higher Plasmodium falciparum

sporozoite rates than uninfected mosquitoes suggesting that filarial parasites

may enhance malaria transmission.

There is therefore the need to

study if concomitant infections of the two diseases in Anopheles vectors

is transmittable to the human hosts living in those areas so that appropriate

integrated vector control strategies that target both diseases simultaneously

may be designed and implemented.

Objective

To determine if concomitant

infections of the two diseases, malaria and lymphatic filariasis (LF) in Anopheles

vectors is transmittable to the human hosts living in those areas.

Key

Findings

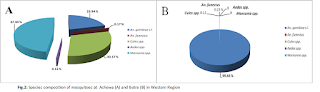

Morphological identification

showed that anophelines were the predominant mosquito species in Butre, whereas

in Achowa culicines predominated (Fig 2).

PCR revealed that in both study sites, Anopheles melas was the most dominant followed by An. gambiae s.s. This may largely be due to the abundance of saltwater in both study sites, as both sites are coastal villages. Anopheles melas is not known to transmit P. falciparum in Ghana.

Occurrence of both W. bancrofti

and P. falciparum infections in Anopheles mosquitoes was

found to be nil. Wuchereria bancrofti prevalence rate in Anopheles mosquitoes

was 0.12 %. Only Anopheles gambiae s.s.

from Butre harboured Wuchereria bancrofti larva, indicating its

ability to pick parasites even at

low densities.

There was no significant

correlation between the nocturnal biting cycles of Anopheles mosquitoes

in Achowa and of those in Butre (r = 0.31; p > 0.05) (Fig. 3).

In both study sites, indoor biting

anophelines were more associated with the part of the community closest to the

coast, whilst outdoor biting anophelines were more associated with that part of

the community which was away from the coast. The part of the community closest

to the coast was more windy by virtue of its proximity to the sea, accounting

for this trend.

Abstract

Africa

accounts for about 33 and 90 % of the world’s burden of lymphatic filariasis

(LF) and malaria respectively. This study set out to investigate if

co-infections of Wuchereria bancrofti and Plasmodium falciparum, the

causative agents of LF and malaria, in Anopheles mosquitoes was transmittable

to the human populations living in areas co-endemic for the two diseases. The

study was conducted in Achowa and Butre, both in the Ahanta West District of

Western Region of Ghana using human landing and pyrethrum spray catches to

collect adult mosquitoes.

Using morphological identifications, and Polymerase

Chain Reactions (PCR), it was found that Anopheles gambiae s.l. was the

most dominant mosquito species in Ahanta West District, with a frequency of

68.63 %. There was no occurrence of concomitant infections of Wuchereria

bancrofti and Plasmodium falciparum in the Anopheles vectors,

probably because female Anopheles mosquito populations collected were not old

enough to carry the individual infections, much less both infections.

Only Anopheles

gambiae s.s. harboured Wuchereria bancrofti microfilaria, an

indication of its ability to pick the parasites even at low densities.

Anopheles mosquitoes at the study sites were found to be more endophagic than

exophagic, and their peak biting times were observed to be towards and after

midnight. Wuchereria bancrofti infection rate in the Anopheles

mosquitoes was found to be 0.12 %. No clear-cut relationship could be

established between malaria and filariasis transmission indices. Eighty-nine

per cent (89.7 %) of the Anopheles mosquitoes collected were parous, and 78.5 %

of them were not older than 6 days.

You Might Also Like:

- Effects of Postpartum Depression on Child Development

- Rural Banking and Evolution of Banking Automation

- 3 Secrets to Stock Investing (stock trading)

- Impact of Risk Based Audit Approach on Implementation of Internal Control System

- Effect Of Facilities Management On Maintenance Culture Improvement In The Ghanaian Real Estate Industry

Some References

Appawu, M. A.;Baffoe-Wilmot, A.; Afari E. A.; Nkrumah, F. K. and Petrarca, V. (1994). Speciescomposition and inversion polymorphism of the Anopheles gambiae complexin some sites of Ghana, West Africa. Acta Tropica, 56: 15 – 23.

Appawu, M. A.;Dadzie, S. K.; Baffoe-Wilmot, A. and Wilson, M. D. (2001). Lymphatic filariasisin Ghana: entomological investigation of transmission dynamics and intensity incommunities served by irrigation systems in the Upper East Region of Ghana. TropicalMedicine and International Health, 6: 511 – 516.

Dunyo, S. K.; Appawu, M. A.; Nkrumah, F. K.;Baffoe-Wilmot, A.; Pedersen, E. M. and Simonsen, P. E. (1996). Lymphaticfilariasis along the coast of Ghana. Transactions of the Royal Society ofTropical Medicine and Hygiene, 90: 634 – 638.

Dzodzomenyo, M.;Dunyo, S. K.; Ahorlu, C. K.; Coker, W. Z.; Appawu, M. A.; Pedersen, E. M. andSimonsen, P. E. (1999). Bancroftian filariasis in an irrigation project communityin southern Ghana. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 4:13 – 18.

Gyapong,J. O.; Adjei, S. and Sackey, S. O. (1996). Descriptive epidemiology oflymphatic filariasis in Ghana. Transactions of the Royal Society of TropicalMedicine and Hygiene, 9: 26 – 30.

.webp)

No comments: